|

Growing Up In Radford 1942-1958 born Ayup mi-duck I arrived in the world on Thursday June 11, 1942, midway through World War Two, so not the best time to come into existence but I wasn't given a say in the matter. It took a nurse with forceps to persuade me to leave my warm, comfortable home of the last nine months or so. This all happened in Nottingham City Hospital at a cost, I'm told, of seven shillings and sixpence as it would be another six years before Mr. Bevan created the NHS. (incidentally twenty-four years later I would pay the same amount, 7/6d, for a license to marry Maggie). money In case the term "severn shillings and six pence" is confusing for those born after 1971 it may be timely to explain non-decimal or “Old Money“ from the start. It’s quite straightforward: instead of pounds and pence, you had pounds, shillings and pence, shown as £ s d (“d” stands for pence, obviously). There were 20 shillings in a pound and 12 pennies in shilling and 240 pennies in a pound. I can't imagine why anyone would want to change it. The coinage was different too. There was the farthing (copper, worth a quarter of a penny). The ha’penny (Copper, worth half a penny) and the penny (copper, worth a penny). Then came the Thre'penny bit (brass, worth three pennies), the tanner (silver, worth six pennies), the bob or shilling (silver, worth 12 pennies). The florin or two bob piece (silver, worth two shillings) and the half-crown (silver, worth two shillings and six pence). The crown (silver, was worth five shillings). Then the paper money: ten bob note (ten shillings) pound note and five-pound note (you didn’t see many fivers in Radford, I never saw one) So, if you bought an item costing one pound, nineteen and eleven (£1/19/11) you would get one penny change from two quid. Simples! Having said that, very expensive goods were priced in guineas. There wasn't a guinea coin or banknote, a guinea was simply one pound and one shilling, making the item look cheaper (a fur coat priced at 20 guineas would cost you 21 pounds).

coinage in the 1940s babyhood Unlike today, the question of gender in 1942 was dead simple. I was a boy and always would be, simply because I had a “tidley” - had I been born without a tidley I would be a girl. Being a boy meant I would have short hair and wear trousers so that everyone would know I was a boy without having to check if I had a tidley or not; girls had long hair and wore frocks. The dress code for new-born babies, however, was for both boys and girls to wear frocks. To avoid confusion boy’s frocks were blue while girl’s frocks were pink, except for their very first frocks which were white because ultrasound hadn’t yet been invented and without it their gender wouldn't be known until they were born.

me in a frock Having babies wear frocks may have made the business of nappy changing easier, I don’t know. I do know that having one’s nappy changed was no fun. A wet but warm nappy is comfy and the smell not too bad if left undisturbed. But when Mam removes it exposing my wet bottom to the cold air and the full stench of its contents are released, no one can blame me for making my displeasure known. My nappies were made of terry towelling which can be washed and re-used over and over until they wear out and disintegrate and return to nature. Sadly, one day Mr. Pamper would inflict on the world his disastrous but highly popular products that far outlast their wearers and may one day completely cover planet Earth. My first public engagement was held on July 12th a couple of hundred yards down the street at Christ Church... my Christening. Mam had originally intended to name me Albert after her dad and elder brother, but somehow when asked to name me it came out as Paul. Even Mam couldn’t say why she said Paul instead of Albert which ended up being my middle name.

my christening certificate parents I was Mam’s first baby and she was advised by the hospital doctor not to have any more children on account of her poor general health and age of 36. So, no siblings for me, despite my future requests to Santa for a little brother. Of course, before I even thought of making an appearance, Mam had needed to find hreself a husband. Otherwise I would be "illegitimate" and would have that recorded on my birth certificate. You had to get married before having a baby or you'd be the talk of neighbourhood. Mam's maiden name was Ethel Brown. She was born on New Year's Day 1906 (her mother was also born on New Year's Day), but she lost both of her parents and her older brother when she was only seven years old. In those days, orphans had to hope someone would "take them in," or else they risked becoming street urchins - there were no official adoption or fostering services. Mam's grandma was in the workhouse, and she had no other family members who could take her. Fortunately, Ada and Horace Place, a childless couple who lived round the corner, gave her a home - on the condition that she did most of the housework in return for their kindness. This included getting up first in the morning to light the fire for them.

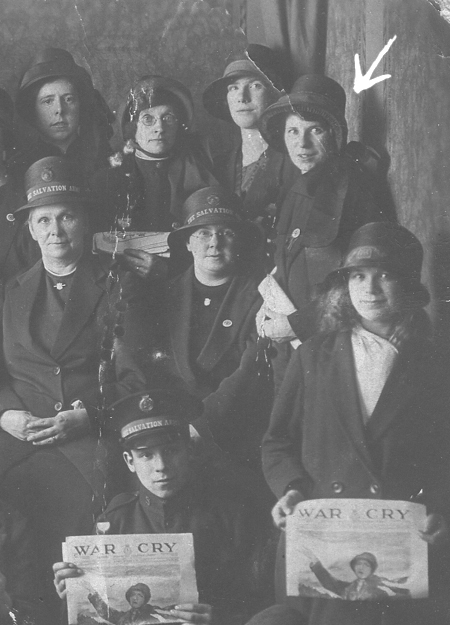

mam aged 13 at school When Mam left school to work in the mill as a bobbin winder, her wages were taken by Ada and Horace, who allowed her to keep a shilling - out of which she gave sixpence to the Salvation Army, her only social life at the time. Despite working long hours at the mill, she still had chores to do at home, leaving her very little time to meet young men. As a result, she remained single into her thirties. Marriage became the only way she could escape from Mr and Mrs Place and start a family of her own. Jack Chambers, a widower who was 29 years older than mam, lived next door to Mr. and Mrs. Place. Ada cooked meals for him and sent Mam round to deliver them to him. They got on well and eventually decided to marry despite the age difference. Ada was not pleased as she would lose the money Mam brought in and she would have to do the work herself that Mam had been doing for free. Ada and Horace refused to go to the wedding and on Mam’s wedding day Ada said she hoped Mam would drop dead at the altar. Even after this Mam continued to be grateful to them for taking her in and even had me call them grandma and grandad.

Mam and dad on wedding day at Shakespeare Street Registry Office our house My home for the next sixteen years was in Radford - a very poor district of Nottingham. 20 Ronald Street was originally a back-to-back terraced house with three floors, each containing two small rooms. One family would live in the front three floors and another in the back three floors, which were separated by a shared staircase. However, by the time Dad lived there, it had become a single house with six rooms. We had our own lavo in the backyard and a single cold-water tap in the kitchen. There was no electricity on the top floor, but the other four rooms and the staircase enjoyed a single light bulb each. There were no plug sockets - we had no electrical appliances. From the street, the front door opened straight into the front room - the parlour - but everyone used the back door into the kitchen, where we spent most of our time. The kitchen and parlour were separated by the stairs leading up to the bedrooms and further stairs to the top - the attic floor - which wasn't used except to store a couple of large chests. I didn't like going up there because it had no lights, and probably the bogeyman was lurking there. On the middle landing, Mam and Dads bedroom at the front of the house contained a double bed and a large mahogany chest of drawers and wardrobe plus a small dressing table. My bedroom was at the rear with a single bed, small wardrobe with matching dressing table and chest of drawers, all in oak. Mam also kept her treadle sewing machine in my bedroom as there wasn't room for it in the kitchen. The bedrooms were not en suite, so if, during the night, one needed to answer the call of nature, nobody wanted to go downstairs, through the kitchen, out the back door, and across the backyard to the lav. No - for that eventuality, we had a chamber pot, referred to as "the po" in polite company, or the "guzunder" in less polite company (because it guzunder the bed). Downstairs, the parlour had a sofa and matching armchair also a chair that looked a bit like a deck chair on steroids which converted to a bed for when I was poorly. Otherwise the parlour was only used at Christmas. The kitchen, looking out onto the back yard, also served as living room, bathroom, playroom and dining room. Like all the rooms in the house, it was very small - not much bigger than the average garage. There was a small square, bare-wood dining table with a couple of wooden chairs, a medium sized wing back chair for Dad and a small armchair for Mam. I had the choice of any bit of floor I fancied or the grey upholstered footstool on casters. In the absence of TV, the fireplace served as the focal point of the room. All the rooms - except the attic - had fireplaces, but aside from Christmas, only the one in the kitchen was regularly used. Despite burning coal (shock-horror), it was surprisingly eco-friendly. A small grate in the centre, made smaller still by adding fire bricks to conserve coal, was flanked by a water boiler on the left and an oven on the right. The grate also featured a fold-down rack to hold a pan or kettle. Thus, our little coal fire heated the room, provided hot water, baked food, and boiled the kettle. And if you fancied toast with your tea, you simply stuck a slice of bread onto a toasting fork and held it in front. I loved watching the burning coal form ever-changing patterns, imagining caverns and monsters in its glowing depths. In the recess to the left of the fireplace was the food cupboard, and in the right-hand recess stood a gas stove. The "coal hole" was the space under the stairs, hidden behind a curtain. Between the back door and the window, we had a butler sink fitted with a cold-water brass tap. If hot water was needed, it was ladled from the fireside boiler - or, in summer when the fire wasn't lit, boiled in a kettle on the stove. ronald street Ronald Street was a short, cobbled street between Ilkeston Road and Denman Street, home to M. Dick & Son, coffin makers; a chip shop; the Goodwood furniture factory; Christ Church and its graveyard; and the General Havelock pub. The rest of the street consisted of flat-fronted terraced houses opening directly onto the pavement. Our house was midway between the chippy and the furniture factory. Goodwood had designed a semi-circular settee called the Tele-Circle, so the whole family could sit together and watch that new-fangled television thingy. They had a showroom on Denman Street.

telecircle The entire street - including the coffin makers, chippy, factory, pub, and church - was demolished in 1958 as part of Nottingham's slum-clearance project. Only the graveyard remains, as a rest garden. On the road alongside the churchyard, there was an air-raid shelter. We never went in it. Dad said that if he was going to be bombed, it might as well be in the comfort of his own bed. Mam stood with me under the stairs, as that was considered the safest part of the house - unless, of course, there was a direct hit. Thankfully, the Luftwaffe managed to miss our street. Babies couldn't wear gas masks, so there was a contraption you were supposed to put the baby in and seal it up. I screamed so much every time Mam tried to put me into it that she eventually gave up. Thankfully, the Luftwaffe didn't gas us either. back yard There were no gardens in Ronald Street, the only greenery to be found was in the graveyard. At number 20, though, we did have our own back yard enclosed by a picket fence. Some houses just opened out onto a communal space with a row of lavatories at one end. Our yard was paved not with concrete but with real flagstones. Sometimes Mam gave me an old paint brush and a bowl of water for me to "paint" pictures on them. When the water dried of course the "pictures" vanish ready for next time. Was this a sign of what I was to become? There was a gate onto a passage which linked the other houses and led out to the street. In the yard was kept the tin bath hanging on the kitchen wall, the dolly tub, ponch and mangle for washing clothes and the dustbin which wasn't wheelie - the bin men had to carry it along the passage and out onto the street. Not that there was ever much in the dustbin. Nothing came in plastic packaging in the 1940s and any waste paper, cardboard or wood went on the fire. Scrap food, peelings, outer leaves etc. was put in the pig bin at the other end of the passage which was periodically collected by a farmer. The only landfill was ashes and empty tins. To one side of the gate was the brick built lavo. The cistern was high on the wall and was flushed by pulling a chain. Toilet paper was cut up squares of newspaper strung and hanging on a nail. Let's face it - who's going to pay good money for paper to wipe their arse on!

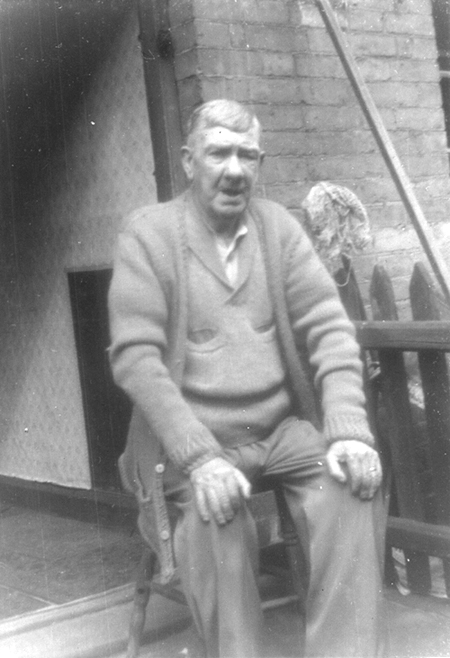

dad enjoying the sun in the back yard garden Later when Dad had retired, he spent much of his time sitting in his chair, facing the window to the backyard. Mam thought it would be nice for him to have a garden view, so we collected old bricks from the bomb site on Denman Street and stacked them two high in front of the lavo wall, creating a space about a foot wide and three or four feet long. Around that time, I had lumps on either side of my neck - enlarged glands, doctor Hickton said - which meant fortnightly sun-ray treatments at the children's hospital. There I would lie on a bed under a sun lamp. To get to the hospital, we walked across the Forest, gathering soil in our hankies on the way for our little garden. Mam bought seeds for daisies, snapdragons, and sweet peas to climb the lavo wall. We ended up with the only garden in Ronald Street! booze The General Havelock got demolished before I was old enough to see inside. In them days days pubs didn't allow children in. The only food you'd get was a bag of crisps and maybe a cheese and onion cob if you were lucky. Ale got delivered in proper wooden barrels on a cart pulled by shippo's 'osses (two huge white shire horses). Dad often sent me with a quart bottle to the beer-off on Boden Street. The beer was pumped into a large pewter jug and then poured into my bottle using a big copper funnel. The fact that I was hardly big enough to see over the counter and was buying booze didn't seem to bother anyone, Dad also sent me to buy his woodbines. I was never asked to show ID. Until the introduction of betting shops in 1960 it was illegal to bet on horses except on the race course. That didn't stop anyone having a flutter though - there were plenty of illegal back-street bookies like Moggie who lived across the road from us. Dad would study his paper, write his choice on a slip of paper and send me across to Moggie to place his tanner (6d) each way, thus involving me in an illegal activity. Mam didn't drink and only went into pubs when she was with the Salvation Army "pub booming" - singing hymns and selling War Cry magazines - in the hope of saving souls. How many souls Mam saved is anybody's guess, but good on her for trying. She told me that no matter how rough the pub was, she was always treated with respect, and anyone swearing would be reprimanded by the other drinkers.

Mam in the Salvation Army relativity Relatively few relatives were in relatively regular contact - no one had phones and social media was restricted to standing on the doorstep gossiping with neighbours, but I did have some relatives. Mam was Dad's third wife - some blokes never learn. When his first wife died, he married her sister and had a son, Jack, and a daughter, Flo. Eventually, his second wife also passed away. Neither of my half-siblings approved of his marriage to Mam. Flo and her husband George, an electrician, were well off by Radford standards. When Flo and George got a television set, we'd go to their house on Sunday evenings to watch What's My Line on the BBC. Their house was a modern bay-fronted semi with gardens front and back, nothing at all like our humble abode.

Flo and George in their posh house Occasionally, Mam and me would visit one or another of Mam's sisters for tea. It was always pretty boring for a kid - my toys were at home, my playmates were at home, and grown-up gossip didn't interest me, obviously. Plus, I had to be on my best behaviour. Because Mam was the youngest of her sisters and had me late in life, all my cousins were much older than me - and many were already married. Aunt Violet, though, had a grown-up daughter, Edna, who still lived at home. Edna had a black-and-white terrier called Spot, so at least I had Spot to play with when we visited. They also kept chickens in the back yard. They lived in West Bridgford, south of the river and considered a little bit posher than the rest of Nottingham. We used to refer to it as "Bread and Lard Island". Because they lived close to the river Trent we sometimes picnicked on the river bank by Wilford Toll Bridge. I would paddle but Edna was able swim over to the far bank and back, I promised me-sen that one day I too would swim across the Trent, and when I was much older I did swim across quite often. It was common then for people to swim in the river and usually on a nice day there would be lads jumping and diving from the Suspension Bridge, not that I was ever brave enough to do that. Visiting aunt Violet involved taking the trolly-bus to Trent Bridge but aunt Mable lived in Radford so we walked there. When she was younger aunt Mabel had pricked her finger on a needle which became infected and resulted in her left hand being amputated just above the wrist. It fascinated me to watch her do stuff one-handed - it didn't seem to restrict her at all and she boasted that she could still give the kids a good hiding when required. She had one son and three daughters, all now grown up. They were Peter who I never met because he lived in Wales, Doris, Mary and Ethel (Ethel was always called "young Ethel" even when she was a pensioner so as not to be confused with Mam).

aunt Mabel's kids For a while cousin Mary came to live with us in Ronald street with her friend Rene. They had the parlour. Rene had short hair, always wore trousers and drove a bread delivery van so, in my innocence, I assumed Rene was a bloke. One day at a family wedding I saw Rene in a skirt. Shocked, I told Mam, who then informed me that Rene was actually a woman. I was a bit flummoxed but I liked Rene, she was good fun and sometimes let me ride in her bread van which was electric like a milk float. It's never been a crime for women to be - well - different. The word "gay" at this time meant "happy/carefree" and I didn't know another word for what Mary and Rene were because such things weren't spoken of, at least not in front of me so I'll say "odd". (Odd men, of course could be put in prison). Mam had no problem with an odd couple living in our house. Even so Mary was persuaded by her family to undergo "therapy" which supposedly cured her of being odd. Personally, I doubt Mary was all that odd in the first place, since she then left Rene, married a chap and had six kids. My only uncle was Ernie who once took me to a Notts County football match. I was not impressed and asked him why I couldn't join in and kick the ball. Where's the point in just standing there watching others have all the fun. That was my first and last visit to a football ground. tea or tea Almost everything was still rationed, so when inviting someone round for tea, they would be asked to "bring your own tea and sugar, and your own bread and butter." Everyone drank tea. You wouldn't ask "tea or coffee?" - just "how many sugars?" The nearest thing to coffee was Camp (coffee and chicory essence), which we had only very rarely and certainly wouldn't have offered to visitors. Of course, tea didn't come in bags to be bunged in a mug. No, it came loose in packets and was brewed in a teapot - one teaspoon per person. The teapot often wore a tea cosy to keep the contents warm for longer. You allowed a few minutes for it to mash, then poured it - using a tea strainer to catch the leaves - into teacups on saucers, not mugs! Milk first, then tea, and finally sugar - we done it proper in Radford. If it was too hot, you poured a little into the saucer and blew on it. Most people had sugar in their tea, I always had two teaspoons of sugar in my tea, so it's no surprise that by the time I left Radford, most of my molars had already left years earlier. playing When I came along, the neighbours - seeing how wonderful Mam's baby was - seemed to want one too. At least, that's the only reason I can think of for why there were six kids around my age living next door to each other: three on our side of the street and three on the opposite side. Across from us lived Shirley, next to Terry, next to Tommy. On our side were Jilly, then Barrie, then me. Kids mostly played outside, usually on the street. We dug a little hole between the cobbles to play marbles - don't try this at home, kiddies. Nobody on our street owned a car, except the boss of the furniture factory. He had a shiny black Wolseley with mudguards, headlamps, bumpers - in other words, a shiny black climbing frame. At least it was, until Mr. Towle spotted us. Luckily, kids can run faster than factory bosses. One day I nearly became a customer of Dicks, the coffin makers. Cars were a rare sight on Ronald Street, which is why we played on the road so much. But one afternoon I dashed through the entry passage without looking, just as a car came along. It screeched to a stop barely two feet from me. I stared at it, promptly peed myself, and shot straight back home. We had plenty of other games. As well as marbles, we did handstands against the wall, the girls tucking their frocks into their knickers. Sometimes two mothers would stand on opposite pavements with a clothesline stretched across the road so the girls could do in-line skipping. Us boys played piggy-in-the-middle and dobby-off-ground. Outside our front door stood a gas streetlamp painted corporation green - in other words a corporation-green climbing frame. Our favourite playgrounds were two bomb sites on Denman Street we called "the buildings." They were perfect for cops-and-robbers or cowboys-and-Indians. None of us wore jeans back then; boys stayed in short trousers until they went to big school at eleven. Scabby knees were a badge of honour, proof of a good day's fun on the buildings. We never had watches either - we played out until dusk, or until somebody's mam called them in for their tea. The nearest park, "the rec," was about a third of a mile down Ilkeston Road. It had swings, a turntable, and a slide. One day Tommy, Barrie and me were playing on the slide when a couple of kids turned up with a candle. They said if you rubbed candle wax on the slide it made you go faster. At first it slowed us down, but after a few runs - polishing it with the seat of our pants - it turned into a super slide. When we'd had enough, we sat and laughed as unsuspecting little kids whizzed down and flew off the end. We always went to the rec without our parents, but there was a park keeper who kept an eye on us. Misbehave and we risked a clip round the ear'ole from the keeper. It was on the rec that I suffered my first broken nose - from being hit by a swing. toys Indoor games were Snakes and Ladders, Ludo, Draughts, and Tiddlywinks. Mam played games with me, but not Dad - I can't blame him, given his age. I had toy soldiers, cowboys and Indians (all made of lead!), an Austin A35 Dinky car, a wind-up train set, and a Meccano set. I had a Chad Valley cowboy outfit with hat, holster and silver colt 45 with pearly handle, just like Roy Rogers. It fired rolls of caps. My soft toys included a teddy called Ted, an elephant called Elephant, a lamb called Lamb, a monkey called Monkey, and a dog called Patch. The monkey was a Christmas present one year when I'd asked for a brother - Santa obviously had a sense of humour. Apart from my toys, there were many interesting things around the house that I played with. It may be that, working in furniture removals, Dad had acquired some odd items that people didn't want to take with them. There were two antique police truncheons painted with insignia and crests, and I'm quite sure Dad had never been a constable. There were also several medals that weren't his, and a pair of pince-nez glasses on a gold chain. A couple of football rattles too, though as far as I know, he never went to matches. We had a wind-up record player with some 78rpm records, including "Deutschland Uber Alles" and "Stille Nacht" (the German national anthem and the carol "Silent Night" in German), along with records by The Ink Spots - an African American pop group - and all sorts of other music. I was the only one who played the records, but each time, after I'd played two or three, I became fed up with having to wind it up after every one.

dad at work Mam taught me to knit and I knitted Ted a jumper and a pair of shorts. I also learned how to darn socks and do embroidery - but please don't tell anyone or they'll call me a sissy. There were no male influences around me to encourage more "manly" pursuits. I wasn't allowed to have friends in the house to play because Dad wouldn't like it. Even at my birthday parties there were no children - only aunties and grown-up cousins. sunday school Playing outside on Sunday wasn't allowed for me. Mam believed Sunday should be kept holy; I could go for a walk, but playing in the street was a no-no. At first Mam continued to go to the General Booth Memorial Hall in Sneinton, the Salvation Army church, and she took me with her. I enjoyed the brass band, but when it came to sermon time, the children were taken to another room for Sunday school. After a while Mam stopped going, and I was sent instead to Deligne Street Methodist Church Sunday school, which was nearer home. On the way there, I passed Aunt Mary's house, and I was instructed to call in and say hello on the way back. Aunt Mary's only daughter had been run over by a horse and cart some years before. Even though it was Sunday, she was always surrounded by a pile of lace, draw-threading it. Each week she gave me a thre'penny bit. As far as I know, I was the only kid in the street who went to Sunday school. At the Sunday school anniversaries, I had to learn a poem and stand up to recite it.

Sunday school anniversary 1951. I'm on the right with white shirt and dark tie baths At first, Mam would bring in the tin bath and place it in front of the kitchen fire. This was fine when I was little, but as I got older, privacy - or rather, the lack of it - became an issue. In Radford, no one locked their doors except at bedtime or when going out. Eventually, I was no longer willing to have neighbours popping in for a chat with Mam while I was in the bath. Fortunately, there were public baths nearby, and every couple of weeks or so, if I needed one, I was able to enjoy a bath in private for just a few pence. laundry On Sunday, I wore my "Sunday best," but for the rest of the week, I wore my school clothes, which were also the clothes I played in. Our school didn't have uniforms - they would have been too expensive for Radford families to buy. Every Monday, I had clean clothes, including underwear, because Monday was washing day. Mam washed our clothes in the dolly tub with washing powder and hot water, agitating them with the ponch. Badly stained items were scrubbed with washing soap on the washboard. The clothes were then rinsed in fresh water with a Reckitts Blue bag added - to improve whiteness - before being put through the mangle to squeeze out most of the water. Finally they were pegged out on the washing line. A prop was used to raise the washing line, but not a fancy expanding plastic coated one from China. No, it was simply a length of one by two inch timber with a "V" cut into one end. Incidentally, a prop was also employed to tap on bedroom windows by the Knocker-upper as few people in our street owned anything as high-tech as an alarm clock. This was all done in the back yard, weather permitting. If it rained, Mam did the washing in the public wash-house next door to the public baths.

public wash-house ironing Tuesday was ironing day. Clothes were ironed using two flat irons; while one was being used, the other was heating up on the gas stove. To create steam, a damp tea towel was placed over the item being pressed during ironing. Later, Mam was given an electric iron. Since there were no plug sockets in our house, the iron had to be connected to a bayonet fitting and plugged into the light socket. It worked well enough, though it meant the iron wasn't earthed. Thankfully, Mam never got electrocuted. cleaning products In Radford, we had no bathroom cleanser, kitchen cleanser, all-purpose cleanser, anti-bac cleanser, miracle spray cleanser, or wonder glass cleanser. None of that and without TV adverts assuring Mam that she couldn't possibly do without them she was blissfully unaware of her needs. What we did have was soap powder for clothes and pots, a block of soap for scrubbing both shirts and floors, and good old carbolic soap for washing and bathing. That was the lot. For air freshener, we simply opened a window. For deodorant - well, you either washed, or you stank. There was no vacuum cleaner, washing machine or carpet shampooer in sight, the dishwasher was me. We just had a brush and dustpan, a mop and bucket, a scrubbing brush, and a duster. And yet, somehow, Mam managed perfectly well - without a cupboard full of plastic bottles all promising to make everything sparkle, and without a load of electric gadgets. Our house was always clean and so was I - at the start of the week anyway. shopping There were no supermarkets in mid-20th century Radford. For meat we went to the butcher, for fish the fishmonger. Fruit and veg we bought from Taylors the green-grocer. Other groceries we got from Home and Colonial. Very little came pre-packed - sweets and biscuits were sold by weight (Mam usually bought broken biscuits which were perfectly good to eat but cheaper). Sugar was weighed into thick blue paper bags with the tops folded over - no sticker. Cheese was cut from the round with a cheese-wire. Butter and margarine was scooped from the barrel, weighed, shaped into a block, and wrapped in greaseproof paper. They were not branded; for instance, it wasn't until 1954, that Stork margerine was once again sold in its own wrapper. National Dried Milk was the only option for feeding babies who couldn't be breast-fed - I was put on National Dried, as Mam's milk wasn't nutritious enough and I wasn't thriving as I should. Everything was rationed, so as well as money you also needed coupons to buy food. There were no such things as loyalty cards. However, it did pay to be a regular customer - for example, one day Mam sent me to Home and Colonial for sugar. The assistant told me to tell her that there were tins of tomatoes under the counter for regulars. I did, and Mam sent me straight back to get a tin. Things like tins of tomatoes and other imported produce were as rare as hen's teeth just after the war. Goods were delivered to shops not in plastic, but in sacks or wooden boxes. Shopkeepers were happy to give customers boxes to chop up for kindling - Mam never bought firewood. We saved our newspapers, and the ones not used to light the fire or cut up for toilet paper were given to the chip shop for wrapping fish and chips. It wasn't thought of as recycling, just common sense. Coal was delivered weekly by the coalman in a small wooden wheelbarrow from his yard around the corner on Denman Street. It came in a hessian sack, which he carried in and emptied into the coalhole under the stairs. Occasionally, he got grief from Mam if she thought there was too much slack (coal dust) - or, at the other extreme, a huge lump that was difficult to break up. finance Mam and Dad didn't have a bank account, and I doubt many people in Ronald Street did. We didn't get bills. Before Mam spent anything the rent was put aside to be collected by the rent-man (rates were included in the rent). Club money for Clays clothing shop was collected by the club-man, Mr. Hollis. We had a Rediffusion wireless set on which we could get the BBC Light Programme, BBC Home Service, and BBC Third Programme. The man from Rediffusion collected our subscription money. Gas and electricity were paid for by putting coins into the respective meter. I took the Christmas didlum money to Mrs. Vinerd in Carlton on the number 39 trolley-bus. Everything else was paid for in cash as and when Mam could afford it. flea pit The "flea pit" or "bug 'utch" is what us kids called the Orion picture house on Alfreton Road. For sixpence on a Saturday afternoon, we were treated to a main film, often a cowboy film. There would also be a short film - Laurel and Hardy, The Three Stooges, or Old Mother Riley, for example. Then came a cartoon, such as Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, or Tom and Jerry. Finally, there was the serial, featuring a superhero like Batman or Superman, always ending with a "cliffhanger" to make sure we came back again the next week. The films we saw on Saturday afternoons were gloriously non-PC and non-woke. My favourite cowboy was Roy Rogers, with his horse Trigger. Roy's films always ended with him riding into the sunset, singing a cheesy country-and-western song. Another favourite was The Lone Ranger, who had a partner named Tonto - a friendly "Red Indian." (Back then, "partner" meant friend and helper, not the modern-day meaning of the word.) The quirkiest character to me was Hopalong Cassidy, who broke the mould by wearing a black hat. Traditionally, the good guys wore white hats and the bad guys wore black ones, so us kids always knew when to cheer and when to boo. Hopalong had a limp from being shot in the leg - hence his nickname. We didn't watch quietly - cheering the good guys and booing the bad guys. At one point, news went around that Lenos, a picture house in Basford, was letting kids into the Saturday afternoon matinee in exchange for either one two-pound or two one-pound empty jam jars. It was quite a walk over to Basford, but it meant we got in the pictures for free. Mam sometimes took me to the pictures on a Thursday evening, though never to the Orion. Instead, we went to the Ilkeston Road Picture House, which was a little more respectable. The only film I remember seeing there was The Glass Mountain, which I hadn't expected to like but turned out to be really good. As well as the main film there was always a short film and a newsreel. I reckon that's good value for 10d. Between the two films adverts were shown and the usherette came round with a tray of ice creams, suckers and Kia-Ora drinks. Sometimes people came in after the film had started and were shown to their seat by an usherette with a torch. Smoking was allowed in most buildings and cinemas were no exception. People didn't seem to mind watching films though a haze of tobacco smoke.

Orion picture house sucker sticks Dad worked at Dalgliesh furniture removers but when he retired, Mam got a job at Pearson's ice cream factory. She was a sucker-stick-sticker-iner, putting the sticks into suckers (ice lollies, if you're not from Radford). The area where she worked was next to the main gate, and on very hot days they kept the door open. Sometimes I would watch her working until somebody took pity on me and brought out a sucker or an ice cream. lodgers After Mary and Rene had moved out of the parlour, we had new lodgers: Cathleen and her husband, Stephan, who was Ukrainian and unable to return to Ukraine for political reasons. They had two grown-up sons and a boy about my age. They lived in the parlour and used the two attic rooms as bedrooms. Cathleen and her family had to fetch water from the tap in the kitchen and pass through to reach the lavo in the backyard. The last nine years in Radford were not ideal, to say the least. In effect our house had reverted to being back-to-back again. The two grown-up lads were heavy gamblers and had enough money to place large bets on the horses. They encouraged Dad to place bigger bets than he was used to, which annoyed Mam, who felt he should contribute more to the housekeeping. Dad was now retired, and, according to Mam, seemed to think his pension was all his. Looking back, I think it's possible that Mam was at an age where she was experiencing ladies issues that nobody ever talks about. Dad spent all day sitting in his chair in the kitchen, and Mam just became stressed. Eventually, she decided that me and her should move up to my bedroom. Everything else remained the same: she still looked after Dad - cooked meals, cleaned, did his washing - and the sleeping arrangements didn't change. The only difference was that Dad spent his days downstairs in the kitchen, while Mam and me spent ours upstairs in my bedroom. While I'm sure that Mam felt a deep affection for Dad, on reflection I believe their marriage was less about love and more about mutual convenience. Dad was cared for in his dotage, while Mam got me. If this was the case, I must say that Dad got the better deal. There had never been much interaction between Dad and me, so the new living arrangements were fine as far as I was concerned. Dad never took me anywhere, apart from taking me to the barbers. He didn't come on picnics, holidays or visits to relatives. When I needed to pass through the kitchen, he didn't speak to me, and so I didn't speak to him. However, it did sometimes feel as though it was Mam and me who were the lodgers. dad One of my biggest regrets is that I didn't talk to my dad. I'm pretty sure he was quite a character and lived an interesting life. All I know of him is what Mam told me - and some of that may have been Dad making it up. I do know he was born in Awsworth on January 8, 1876, and that he worked down the pit, as did his own father, who was killed in a roof collapse. At some point, he emigrated to Canada to work on building a railway line. When the work was completed, he declined an offer of a return ship to England. Instead, he crossed into America and lived in Seattle. In March 1910, he applied for US citizenship; I know this because I have the original Declaration of Intention. The story he told Mam was that he travelled around by hiding in freight trains, worked in a gold mine, and was eventually deported for making moonshine during Prohibition. You know what? I choose to believe it.

dad when a young man good times We didn't have many holidays but my favorites were the couple of timess I was taken to Blackpool, by Mam and her best friend, Nellie who lodged next door to us with Mrs Pick and her son Barrie, who was my best friend. Both times we stayed at a boarding house owned by "aunty Ruth" who was a relative of Nellie. I rode on a donkey, built sandcastles with my bucket and spade and played with my beachball. I Loved watching the old trams going along the promenade. One day on the beach I managed to wander off and get lost and was taken to the police station. Mam must have been frantic looking for me and all I said to her when she came to pick me up was "Have you got the banana aunty Ruth gave me". There were two or three holidays in a caravan at Ingoldmells near Skeggie (Skegness). The August bank holiday was spent blackberry picking at Hemlock Stone. We took jam jars with string handles to put them in. Mam told me not to pick the ones high up, as the birds would need them. Sitting on a blanket surrounded by bracken, with no sound but the buzzing of insects, we had a picnic of egg sandwiches and tea from a flask. Other bank holidays, weather permitting, were spent picnicking at Wollaton Park, Highfields Park, or the Arboretum. The best picnics, though, were when we went to Trent Bridge and sailed on a pleasure boat to Colwick Pleasure Beach, which had an artificial sandy beach by the river for building sandcastles. To me, it felt just like being at the seaside.

off to build some sandcastles with mam school Upon reaching the age of five, all children had to begin their education, whether they wanted to be educated or not. It was not an option as it is today. You didn't get to choose your school either - you simply went to the nearest one, good, bad, or indifferent. My first school was Douglas, on Ilkeston Road, opposite the churchyard at the end of our street. So I didn't have far to go. Douglas School, a large, fearsome Victorian building, was my school until I was eleven. There was not much I learned at school that proved useful in life, other than reading and writing. Arithmetic was my worst subject; I just couldn't grasp numbers, especially mental arithmetic. Long division and algebra weren't too bad, but I can't say I ever needed either after leaving school - especially once pocket calculators were invented. Music lessons always felt like a waste of time for me - I've never been able to sing. When we practiced scales, my do, re, mi just got louder instead of higher. On one occasion, the teacher asked me to stay quiet so she could hear whether the rest of the class was getting it right. And when it came to playing instruments, guess who was given the triangle with instructions to wait until the very end of the tune - and then make a single "ting". School sport was something else I was never going to excel in. In cricket, I always got out before ever managing to hit the ball. I was no better at fielding either, mostly dropping catches, and when I was made wicketkeeper, I stood too close. As the batter swung his bat back, it connected with my nose - the second time I got a broken nose - leaving it permanently left of centre. Now, if I follow my nose I just walk round in circles. At football, I was no "Golden Balls." The teacher would select two captains, who then took it in turns to choose who they wanted on their side. Guess who was always last to be picked, amid a chorus of groans from the unlucky team I would be joining. Douglas was where I learned to read and write. Story time was my favourite lesson, and listening to stories encouraged me to read on my own. The books we had at home were old ones. The Pilgrim's Progress I tried to read, but didn't get very far. Similarly, Tales from Shakespeare by Charles and Mary Lamb was hardly age-appropriate. Aesop's Fables, A Christmas Carol, The Water-Babies, and a book of fairy tales, however, all had wonderful illustrations that I loved. Then, at school, the teacher began to read Treasure Island by R. L. Stevenson to us. I enjoyed it so much that I put it on my Christmas list for Santa, hoping to read it myself. Unfortunately, Santa got confused and brought me Five on a Treasure Island by Enid Blyton instead. (Coincidentally, it was the first Famous Five book and had been written the year I was born.) My initial disappointment soon vanished once I began reading it - I was hooked. I ended up devouring all of the adventures of Julian, George (Georgina), Dick, Anne, and Timmy the dog. I doubt Enid Blyton's books are still found in schools today - too "un-woke" for modern sensitivities - but it was thanks to Mrs. Blyton that I went on to read hundreds of books over time. Alongside learning to read and write at Douglas, I also acquired another very useful skill: swimming. At one point, we were given the opportunity to attend a swimming course at the local baths. The problem for me was that I didn't own any swimming trunks, and Mam couldn't afford to buy any. She solved the problem by unraveling an old woollen jumper and knitting me a pair of royal blue woolen bathers. At the end of the first session, when it was time to leave the pool, some of us children - rather than queuing for the steps - decided to pull ourselves out at the side. One feature of wool is that when it gets wet, it becomes very heavy - so heavy, in fact, that when I climbed out of the pool, my royal blue woolen bathers didn't. After that excruciatingly embarrassing episode, I always left the pool carefully by the steps. Still, I did learn to swim, and I even received my certificate for swimming the length of the pool. All thanks to my knitted, royal blue woolen bathers.

class 3A Douglas junior school. I'm 5th from left, back row clothes Woolen swimming trunks were not the only garment Mam made for me. She also knitted jumpers, scarves, and even socks, often using recycled wool. She once made me a red coat from one of her old coats. Unlike many Radford kids, though, I never had anything second-hand. Clays was a clothes shop on Denman Street that ran a weekly "club". Every week the "club man" would come to the house and collect Mam's club money. Then, at Easter, when the "club was up," Mam took me to Clays and got me fitted out with new clothes for the coming year using the money she had paid to the club man. It was always new clothes at Easter, because it was well known that if you didn't wear something new at Easter, the birds would shit on you. After sorting me out, if there was money left, Mam would have something for herself - but often there wasn't anything left. Then the club started again for the next year. It never occurred to me to ask for clothes or demand something just because so-and-so had one. Mam bought the best she could afford for me and always made sure I looked smart. If I got a tear in something, she mended it rather than let me walk about in torn clothes like some kids wore. New clothes replaced old ones that I had outgrown (these were passed on to Tommy) or that were too worn out to wear any more, not because I fancied something different. "Designer gear" was unheard of then. Shoes that developed a hole in the sole were taken to the cobbler and repaired, not thrown away. Eventually of course, all clothes wear out beyond repair. When they did they went in the "rag bag", there was one for woollens and one for every other fabric. Hand knitted woollies mam would often undo to knit something else with. The rest were saved for when the rag-a-bone-man came by with his horse and cart, to be exchanged for a few pennies or toys like a windmill, bag of marbles, or if there were a lot of wool which was more valuable than other fabrics, a goldfish in a tiny glass bowl. My first pet was a goldfish from the rag-a-bone-man. Mam bought a bigger bowl and some seaweed and fish food for it. We named it Richard. When Richard died he was replaced with another goldfish who was also called Richard - goldfish were always called Richard.

The red coat mam made noel, noel Christmas: I must have been a good boy because Santa came to me every year. On Christmas eve mam gave me a crisp clean pillowslip to hang at the foot of my bed for Santa to put my presents in, but crafty Santa took my clean pillowslip and left my presents in a used dirty one. On the top would be my main present that I had asked him for. A fort one year a garage another. other main presents included a meccano set, a scooter (not electric) and a toy aeroplane which didn't fly but did run along the ground powered by a friction motor. As well as my one main present, there was also a Dandy, Beano or Topper annual, a Noddy or Famous Five reading book and a colouring or tracing book. Often there would be a Cadbury's, Fry's or Rountree selection box and chocolate coins or sweet cigarettes. At the bottom always some nuts and an orange. Christmas eve was the one night of the year that mam lit the coal fire in my bedroom. Christmas presents for adult friends and relatives were quite modest. For ladies, they might include a box of pretty handkerchiefs or a jar of bath salts. Men were usually given a tie, a pair of socks, or handkerchiefs with their initials embroidered in the corner. We always had paper trimmings, tinsel, and a Christmas tree. The tree was about two feet tall, with a dozen or so thin branches on which Mam put cotton wool to look like snow, then decorated it with glass baubles. My favourite bauble was "Mr Moon," shaped like the man in the moon wearing a red woolly hat. I still have it, but it's far too delicate to risk putting on a tree now. The tree had no lights, but at the end of each branch was a little cup to hold candles, like those on a birthday cake. Thankfully our tree never caught fire. For Christmas dinner we always had a chicken - a whole one - sometimes with feathers that mam had to pluck in the back yard. For us chicken was a luxury kept for special occasions. Clarence Birdseye had developed his quick freezing process in the 1920s but frozen food wasn't widely available in shops until the 1950s. We didn't even have a fridge in Radford so everything was bought fresh. There was usually no alcohol in the house except for dad's beer, but at Christmas mam went to Burton's of Smithy Row in town, (a really posh shop in the Exchange Arcade) for a bottle of Sandeman Port Wine; it had to be Sandeman because Mam said only the best would do at Christmas. Mam never went into debt for anything. Grace Vinerd, the wife of the Salvation Army band's bass drummer, ran a didlum club. Throughout the year, Mam paid Grace a regular amount every couple of weeks, which was deposited into a bank account and then returned to Mam for her Christmas expenses.

mr moon big school After failing my eleven-plus exam for grammar school it was decreed that Radford Boulevard Secondary-modern could provide enough education for a job at Raleigh cycles, Players tobacco or the pit. Or as my careers master told me later "leaning on a shovel by a hole in the road". Despite the name there wasn't much modern about the old Victorian pile similar to Douglas. It was here that I learnt the Theorem of Pythagoras. Apparently it was imperative for all Radford children to know that in a right-angled triangle the square on the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares on the other two sides. Using this information our class, with the help of a tape-measure, pea-shooter, protractor and a piece of weighted string, were able to calculate the height of the school's clock-tower. Over several decades since leaving school, not once have I needed to measure anything using the theorem of Pythagoras. After two years at Boulevard we were given the option to change to a new school round the corner which was a comprehensive. Comprehensive schools were a new concept that allowed for those who didn't make it to Grammar school to stay at school an extra year and take the GCE exams. Thus they would leave with the same qualifications as the clever clogs that went to grammar school. To me "Cottesmore Comprehensive" sounded better than "Boulevard Secondary Modern", so I switched. Big mistake. The curriculum was different at Cottesmore which found me trying to do third year French when I hadn't done years one and two. Instead of art (which I enjoyed) it was metalwork (nothing to do with Raleigh factory being across the road of course) and no one asked me about right-angled triangles. In secondary school, classes were not mixed as they were in the juniors. Girls were taught in a separate building. Mostly we were well behaved and respectful to the teachers unlike kids today if programmes like Waterloo Road are to be believed. This may be due to teachers having the option to administer corporal punishment should someone be disruptive in class. "The strap" was an effective deterrent against bad behaviour, I got the strap two or maybe three times and it hurt. The hurt though, was not what made us avoid getting the strap - the main fear was that it might make you cry. As everyone knows, boys don't cry, so if you did, the shame of it was much worse than the physical pain.

doe-eyed and cute teens The doe-eyed cutie that started secondary school underwent a horrible transformation. Yes, I soon mutated into a lanky, spotty, smelly, angst-ridden teenager. I grew quickly, but only upwards, not outwards - the proverbial beanpole. Some people said that if I stood sideways, I wouldn't cast a shadow. All the magazines I read carried advertisements by Charles Atlas in the form of a comic strip, where a skinny lad (the eight-stone weakling) is sitting on a beach with his girlfriend when a beefy guy turns up and kicks sand in his face. The girlfriend deserts the skinny lad to go off with the beefcake. The lad then sees an ad and gets the "Charles Atlas Bullworker" - basically a strong spring with handles at each end. Next, we see the once-skinny lad with bulging muscles; he decks the beefcake and wins his girlfriend back. Throughout my entire teens, I was convinced that if I ever took a girl to the beach, I would get sand kicked in my face because I couldn't afford a Charles Atlas Bulworker. If I couldn't be tough, I could at least do my best to look tough - as well as grown-up and sophisticated - by having a fag dangling from my mouth like Humphrey Bogart. The problem was that a packet of ten Park Drive cost one-and-six (18 old pennies). However, a kindly tobacconist on the way to school was happy to sell us schoolkids single Park Drives at tuppence each. As soon as I was old enough I got myself a paper round, delivering the morning papers before school and the evening papers after school, Monday to Friday. On Saturdays I only had the evening round to do, Sunday was my day off. For this I was paid ten bob. Even so, I sometimes had to borrow a shilling from the pile Dad kept in a drawer for when he needed to feed the gas meter. He never asked me to pay him back, possibly because he didn't know I'd borrowed it.

not Humphrey Bogart crime With no male role model to look up to, an adolescent boy is often inclined to follow his peers, doing what they do even when it can lead to trouble. One evening, a group of us from school roamed the streets of Radford in search of adventure until we came to a wall. Not knowing what was on the other side, we climbed over and discovered a bottling factory with a lorry fully loaded and ready to go out in the morning. It was curtain-sided, which meant we could reach under the canvas and grab some bottles of barley wine. Barley wine isn't actually wine but a very strong beer, around 8-12% ABV. We didn't take much, just a couple of bottles each. We might have got away with it if one lad hadn't taken a bottle to school and been caught with it, the dozy bogga! The police became involved, but the factory owner was reluctant to saddle a bunch of kids with criminal records. Instead of pressing charges, he told us we could spend Saturday morning at the factory sticking labels on Guinness bottles - which we did. dame agnes Even though I had done my penance at the bottling factory, the policeman still came to our house and told Mam what a naughty boy I had been. He advised her to get me to join the Dame Agnes Mellers Lads' Club, to keep me off the streets and out of trouble. The least I could do to make up for the shame I had brought on the family was to comply and join. I loved it - I had a lot of fun and learned woodworking. Over several weeks, I made Mam a medicine cabinet and a jewellery box in solid oak, which I French polished. It was all free; I just had to pay for the wood. Dame Agnes, herself never made an appearance at the club, which was disappointing, however understandable as she'd popped her clogs in the early 16th century. boys' brigade Wednesday nights at the club were Boys' Brigade nights, so naturally, I joined that too. It turned out to be just what I needed. The Brigade was run by an ex-sergeant major who treated us as though we were genuine army recruits ("am I hurting you lad - I should be - I'm standing on your hair"). Of course, it meant Mam had to buy me a uniform, but she never complained. We were drilled in every detail, even down to how to spit and polish our boots. Each week we stood inspection, and woe betide anyone whose uniform wasn't up to standard. We practiced marching in perfect step, changing step mid-stride, turning, wheeling, standing to attention, and saluting. I even tried my hand at playing the side drum, but my lack of rhythm must have betrayed me, as I never made it onto parade with a drum. Instead, I was given the honour of becoming the colour bearer, carrying the flag on parades - I learnt discipline and self-control and stayed out of trouble - Well at least until the 1970s, but that's another story, and I won't be writing about that. in the end In the end, I didn't stay an extra year at Cottesmore School because any GCE exams I might have managed to pass would have been worth diddly-squat unless they included maths - and that was never going to happen. So I left school at 14 and got a job in the rag trade, pressing seams in coats at a tailoring factory in the Lace Market. The real money was made working down the pit, but that was too much like hard work for me to even consider. Two years later, Ronald Street was demolished, the lodgers got a house in Clifton, and we were re-housed in a prefab in Beechdale.

our pre-fab * |